Lists, tuples, and dicts

One of the goals I had in creating Reeborg's World was to have functions or methods that would return some basic data structures, such as Python's lists, tuples, and dicts (and their JavaScript equivalents, if possible), thus giving a starting point to discuss such data structures in an environment that students were already familiar with.

In all the examples below, unless specified otherwise, I used the world Alone to ensure that there is a robot present at position (1, 1).

List

RUR.add_object("token", 1, 1, {'number': 4})

RUR.add_object("beeper", 1, 1, {'number': 7})

print(object_here())

print(object_here("token"))

print(object_here("apple"))

The result is:

['token', 'beeper']

['token']

[]

[info] Why a list?

Using

object_here(), Reeborg can see what kind of objects are present, but does not know how many of each are there. To find out the exact number, Reeborg would need to pick up the objects to count them.

The JavaScript equivalent to Python's lists are Arrays; running the following JavaScript program yields a result that looks identical to the above:

RUR.add_object("token", 1, 1, {number: 4})

RUR.add_object("beeper", 1, 1, {number: 7})

write(object_here(), "\n")

write(object_here("token"), "\n")

write(object_here("apple"), "\n")

Tuple

print("Here:", position_here())

print("Facing East, in front:", position_in_front())

turn_left()

turn_left()

print("Here", position_here())

print("Facing West, in front:", position_in_front())

The result is:

Here: (1, 1)

Facing East, in front: (2, 1)

Here (1, 1)

Facing West, in front: ()

The last value is an empty tuple, which is used to represent a position that does not exist in the world.

We can, of course, assign names to each tuple item.

# facing East at (1, 1)

x, y = position_in_front()

print("x =", x)

print("y =", y)

Which gives the following:

x = 2

y = 1

Note that JavaScript does not have tuples; so arrays are returned instead.

write("Here: ", position_here(), "\n")

write("In front: ", position_in_front(), "\n")

The result is:

Here: [1,1]

In front: [2,1]

Dict

RUR.give_object_to_robot("apple", 3)

RUR.give_object_to_robot("banana", 4)

print(carries_object())

The result is as follows:

{'apple': 3, 'banana': 4}

For JavaScript, a simple object is returned:

RUR.give_object_to_robot("apple", 3)

RUR.give_object_to_robot("banana", 4)

write(carries_object())

yields

{"apple":3,"banana":4}

Note however that if we specify an argument to carries_object, it is an integer (the number of such objects being carried) that is returned and not a dict (nor an object in JavaScript).

RUR.give_object_to_robot("apple", 3)

RUR.give_object_to_robot("banana", 4)

print(carries_object("apple"))

print(carries_object("token"))

The result is:

3

0

Caution: if Reeborg carries no object, the returned value of carries_object() will be 0, and not an empty dict.

Ideas for worlds

In a tutorial that unfortunately has disappeared from the web1, Andres Castano had created some worlds which had the students learn to use Python lists. The premise of the exercises included having to move some rows of strawberry plants to a different location, or move some artefacts from an archeological dig, preserving the information as to the number of objects and their location. For a one-dimensional list, such a world might look like this:

where Reeborg would have to move the stars (with an unknown number at each location) from the recently dug up area to a cleaner location.

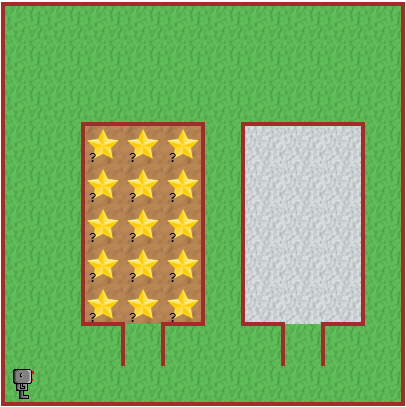

A problem requiring a two-dimensional list might look as follows:

For the first few exercises, students could be given worlds with lists already created, and simply use array indexing to set and retrieve the number of objects at a given location. Afterwards, the students could be asked to create their own lists and use append() to record the number of objects at each location: this would be most effective if the size of the enclosure in which the objects are found could be changed randomly, each time the world is (re)loaded.

More advanced students may be given configurations with multiple types of objects at the same location. They could also be asked to use dicts, with tuples as keys, and other dicts as values such as

archeological_site[(x, y)] = {'star': 3, 'token': 2}

Moving objects to a new location would then mean to use the values found at (x, y) and move them to (x + c, y).

[success] Contribute

If you design worlds using similar ideas, please feel free to share them!

For very advanced students

A much more complex example of a Python dict (or JavaScript object) is that of the "world map". We start with a Python example:

World("Tokens 1")

gps = SatelliteInfo()

gps.print_world_map()

The result looks something like the following:

{

"robots": [

{

"x": 1,

"y": 1,

"prev_orientation": 0,

"objects": {},

"_orientation": 0,

"_is_leaky": true,

"_prev_x": 1,

...

with many more lines printed. For complex worlds, this can be very long. We can access the information as a dict implemented as a Python property for the class.

World("Tokens 1")

gps = SatelliteInfo()

goal = gps.world_map["goal"]

print(goal)

The printed result is not formatted as nicely as the previous "printed" version, but give us the required information.

{'position': {'x': 4, 'y': 1}, 'objects': {'3,1': {'token': 1}}}

[info] French version

En français, une version équivalente du code décrit ci-dessus serait comme suit:

Monde("Jetons 1") gps = InfoSatellite() gps.imprime_carte() but = gps.carte_du_monde["goal"] print(but)

There is also a JavaScript version which is available in both English and French2 as follows:

var goal, map;

RUR.print_world_map();

map = RUR.world_map();

goal = map.goal;

write(goal)

1. It seems to have been partly saved by the Internet web archive at: https://web.archive.org/web/20150118234111/http://ezprog.weebly.com/l11---grouping.html ↩

2. Functions that belong to the RUR namespace are not translated; they are only available with an English name. ↩