JavaScript and Python code pre-processing: the gory details

As far as I know, most if not all Karel simulators implement their own code interpreter, so that students can step through instructions one at a time. However, this is not the case for Reeborg's World. The reason for this is that I wanted for anyone using the program to be able to use any valid Python or JavaScript code, and I am not competent enough to implement a fully-featured JavaScript or Python interpreter. Here is what I do instead.

JavaScript

For JavaScript, I concatenate the code found in the Pre editor (written by the creator of the world) with the user's code and the code found in the Post editor (also written by the creator of the world). Then, I use JavaScript's eval() to execute the program. This can essentially be summed up by:

eval(Pre + program + Post)

During the execution, each time the world changes (e.g. Reeborg changes position using move()), a copy of the world's content is made (which I call a frame) and appended to a JavaScript array (similar to a Python list). When eval() terminates, the content of that array is displayed frame by frame with a user-definable interval (using think()) between each frame; this is done using JavaScript's setTimeout function.

The initial reason why I used a recording of frames was that JavaScript is a single-threaded language which does have a sleep() function - otherwise, I would have likely used this. However, since I use a list of frames, students can not only step forward through the recording but also backwards if they so desire, which would not have been possible using an approach based on the existence of a sleep() function. With the approach used, students can even quickly go through a particular frame using the html slider.

Dealing with JavaScript errors

Reeborg's World uses JavaScript Errors / Python Exceptions to signal the end of a user's program - sometimes after some analysis to confirm that the task was accomplished successfully (or not). So, the code run is closer to this:

try {

eval(Pre + program + Post);

} catch (e) {

analyze_error(e);

}

// If there was not a fatal error:

display_result_frame_by_frame()

// after last frame,

if (world_includes_goal()) {

check_goal();

}

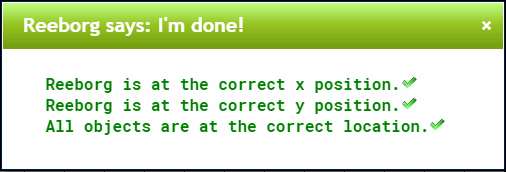

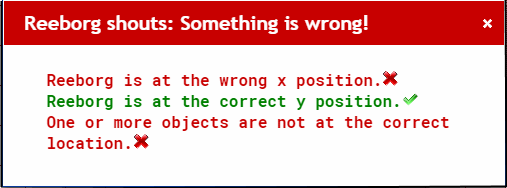

The error analysis and goal checking consists essentially in formatting the information received and presenting it to the user.

Python - no highlighting

By default when using Python, highlighting of a line of code about to be executed is performed. This can be turned off. In this case, processing of code written in Python closely matches how it is done with JavaScript. The Python interpreter used is Brython. Instead of using eval(), exec() is used with something like the following:1

import reeborg_en

globals_ = {}

exec(reeborg_en, globals_) # see note 1 below

program = transform(program)

exec(Pre + program + Post, globals_)

Once again, frames are recorded and playback is done using JavaScript's setTimeout.

The function transform() scans the user's code as a string (i.e., it does not evaluate its validity) and replaces any instance of

repeat n:

block_of_code

by

for count_variable in range(n):

block_of_code

where each required count_variable is chosen to be a unique name in program, and with the additional requirement that int(n) must not raise an exception. Thus int( 2 * 3) would be valid, but int(variable) where variable is a valid Python identifier would not be valid.

Additional processing: non-breaking space

In addition to the above, non-breaking spaces (html or &\#160;) are transformed into regular spaces (ASCII 32). This is to allow users to copy code from a teacher's website or from the API page into the editor and have it executed correctly. Python does not recognize this character as a valid space character, whereas JavaScript does.

The library

The true library module is not the one seen by the student. Here is its true content:2

from browser import window

from preprocess import transform

from reeborg_en import *

src = transform(window.library.getValue())

exec(src)

The function window.library.getValue() gets a copy of the code in the library editor tab and transforms it so that repeat can also be used.

Dealing with Python Exceptions

As with JavaScript, we also do some analysis at the end of a program. The analysis performed is however more extensive. If we find a SyntaxError, we examine the code and attempt to see if perhaps a colon : is missing to indicate the beginning of a block of code, or if parentheses () might be missing in a function call. We also try to identify the line of code in the user's program where the error occurred; however, this is not always reliable since the code executed potentially includes both some additional code in the Pre editor and also some extra lines of code inserted to provide code highlighting and watching variables as described below. We do a similar search for the line number when an IndentationError is raised and try to do the same for a NameError.

Python - with highlighting

When code highlighting is desired, some extra processing on the user's code is done to insert additional statements, each indicating which line or lines of code must be highlighted. For example, with code highlighting on, a user may enter the following program in the editor:

def turn_right():

repeat 3:

turn_left()

def follow_wall():

'''

Useful for getting out of a maze

'''

if right_is_clear():

turn_right()

move()

elif front_is_clear():

move()

else:

turn_left()

while not at_goal():

follow_wall()

and the program actually executed will be the following:

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([0])

def turn_right():

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([1])

for ITERATION_VARIABLE0 in range(3):

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([1])

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([2])

turn_left()

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([4])

def follow_wall():

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([5, 6, 7])

'''

Useful for getting out of a maze

'''

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([8])

if right_is_clear():

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([9])

turn_right()

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([10])

move()

elif RUR.set_lineno_highlight([11]) and front_is_clear():

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([12])

move()

else:

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([13])

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([14])

turn_left()

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([16])

while not at_goal():

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([16])

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([17])

follow_wall()

The function RUR.set_lineno_highlight records the information needed to update the display of the Python code editor, highlighting the required lines of code.

From the various tests I have done, this code insertion seems to be reliable when the user's program contains neither SyntaxError nor IndentationError. However, I consider it to be potentially fragile. If you see an Exception being raised that you cannot explain, you might want to try to turn off highlighting and see if it solves the problem. If it does, please send me a copy of the offending code so that I can improve the extra processing.

Watching variables

When watching variables is enabled, yet more extra code gets added. With both highlighting and watching variables enabled, the simple program

def add_and_print(a, b):

c = a + b

print(c)

return c

add_and_print(3, 5)

gets converted to

def add_and_print(a, b):

__watch(system_default_vars, loc=locals(), gl=globals())

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([1])

c = a + b

__watch(system_default_vars, loc=locals(), gl=globals())

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([2])

print(c)

__watch(system_default_vars, loc=locals(), gl=globals())

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([3])

return c

__watch(system_default_vars, loc=locals(), gl=globals())

RUR.set_lineno_highlight([5])

add_and_print(3, 5)

__watch(system_default_vars, loc=locals(), gl=globals())

Prior to execution of this code, a copy of variables found in locals() is made and copied in system_default_vars; these are assumed never to appear in a user's program. __watch uses the information from the two Python dicts for the main program scopes (local and global) to generate a table of variables and values. Each call to __watch potentially results in an extra frame being created; actually, the content of what would be generated by __watch in a new frame is copied into the previous frame's content to minimize the number of frames created.

Note that the last call to __watch in the indented block occurs before the last line of that block is executed: any change of variables occurring in the last line of code for a given block is unfortunately never recorded by __watch.

[info] A better solution?At one point, Brython apparently had a working debugger as a demo; it no longer works. I believe that a similar approach used in creating Brython's debugger would likely work better and much more reliably, both for identifying which line of code is being executed and what is the current content of

locals()andglobals()than the solution I have implemented.

1. Rather than callingexec()each time, for efficiency I now call it once at the beginning of a browser session, save the result in adictand update thelocals()using the saved result. However, I believe that the above code faithfully describes the basic idea of what is actually done. ↩

2. A similar improvement to that noted in 1 has been made to the code since it was written. ↩