Graphs

[danger] The version on the website may not be compatible with the code presented here.

This will be fixed in the near future.

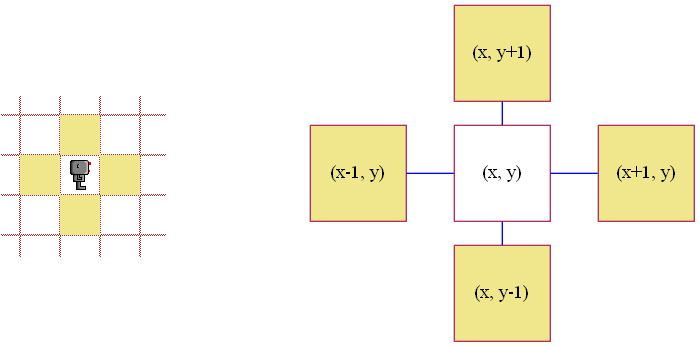

A graph is a set of nodes connected by edges. Below is a screen capture taken while browsing Grids and Graphs from Red Blob Games, showing an example of a graph.

From a mathematics point of view, both graphs are identical, since they have the same number of nodes, connected in the same way by edges -- even though their appearance as drawn look different.

Graph representation of Reeborg's World

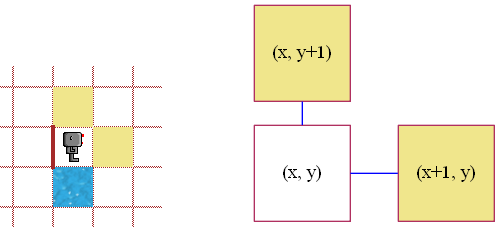

Instead of the usual grid representation of the world, we will use a graph representation where valid locations are nodes connected by edges. Reeborg can move from one node to another (using a move() command) provided that the two nodes are connected.1 We will label each node by a 2-tuple, (x, y) ; the connected nodes will be called its neighbours. Normally, except at the world's boundary, each node has four neighbours:

However, if a location (node) would be fatal for Reeborg, or if its path (edge) would be blocked by a wall, we do not include it in the neighbours.

Python data structure

To represent a world, we use a custom class named Graph() available from the search_tools module. Graph has just a few methods; the only one we need at this point is the following:

neighbours():returns the list of neighbours to a given node, according to rules determined when the instance ofGraphis created.

When creating a Graph instance, we can specify various keyword parameters, each of which may change the representation of a given world by a graph. In particular, we have:

ordered: when set toTrue, the neighbouring nodes will be given always in the same order: east, north, west and south of the position(x, y).robot_body: if specified, this specific robot (body) will be taken into account when compiling the list of neighbours. You may recall that a given robot can carry objects offering a protection against otherwise fatal artefacts. Specifying such a robot (body) ensures that all "safe" nodes for that robot are included in the list of neighbours. Note that the position of the robot does not have to be the same as where we are compiling the list of neighbours.If

robot_bodyis left unspecified, and there is at least one robot in the world when theGraphinstance is created, it will be assumed that the default robot must be considered when compiling the list of neighbours.

More parameters will be defined later. Here are some examples for you to try:

from search_tools import Graph

World("Empty")

graph = Graph(ordered=True)

print(graph.neighbours( (4, 4)))

# -> [(5, 4), (4, 5), (3, 4), (4, 3)]

RUR.add_wall("east", 4, 4)

print(graph.neighbours( (4, 4)))

# -> [(4, 5), (3, 4), (4, 3)]

RUR.add_obstacle("water", 4, 5)

RUR.add_obstacle("fire", 3, 4)

print(graph.neighbours( (4, 4)))

# -> [(4, 3)]

RUR.add_new_thing({'name': 'fire_protection',

'url': 'src/images/token.png',

'protections': ['fire']

})

RUR.add_new_thing({'name': 'water_protection',

'url': 'src/images/token.png',

'protections': ['water']

})

##=== Adding robots, but unordered neighbours

robot_fire = UsedRobot(1, 1, fire_protection=1)

assert robot_fire.carries_object("fire_protection")

robot_water = UsedRobot(2, 2, water_protection=1)

graph_f = Graph(robot_body = robot_fire.body)

graph_w = Graph(robot_body = robot_water.body)

graph_new = Graph()

print(graph_f.neighbours( (4, 4)))

# some permutation of [(3, 4), (4, 3)]

print(graph_w.neighbours( (4, 4)))

# some permutation of [(4, 5), (4, 3)]

print(graph_new.neighbours( (4, 4)))

# some permutation of [(3, 4), (4, 3)]

# default robot is robot_fire,

# which was the first robot added

robot_fire.put()

print(graph_f.neighbours( (4, 4) ))

# -> [(4, 3)]

The Python class Graph() and the method neighbours() are wrappers for the corresponding JavaScript functions which we use in the next section.

[info] Further reading

- A complementary introduction to graphs can be found on the Amit Patel's Red Blob Games site.

- Artificial Intelligence: a Modern Approach, by Russell and Norvig, uses graphs and search algorithms extensively. Some interactive examples, created by Amit Patel, can be found here.

JavaScript version

JavaScript does not have tuples; we thus use arrays with two elements to represent nodes when using JavaScript.

Also, JavaScript syntax does not include keyword-based arguments like we have in Python; instead, we pass an optional object. Below is the JavaScript equivalent to the Python example above.

World("Empty");

var graph = new RUR.Graph({ordered:true});

writeln(graph.neighbours([4, 4]));

// -> [[5, 4], [4, 5], [3, 4], [4, 3]]

RUR.add_wall("east", 4, 4);

writeln(graph.neighbours([4, 4]));

// -> [[4, 5], [3, 4], [4, 3]]

RUR.add_obstacle("water", 4, 5);

RUR.add_obstacle("fire", 3, 4);

writeln(graph.neighbours([4, 4]));

// -> [[4, 3]]

RUR.add_new_thing({'name': 'fire_protection',

'url': 'src/images/token.png',

'protections': ['fire']

});

RUR.add_new_thing({'name': 'water_protection',

'url': 'src/images/token.png',

'protections': ['water']

});

//=== Adding robots, but unordered neighbours

var robot_fire = new UsedRobot(1, 1);

RUR.give_object_to_robot("fire_protection", 1, robot_fire.body);

var robot_water = new UsedRobot(2, 2);

RUR.give_object_to_robot("water_protection", 1, robot_water.body);

var graph_f = new RUR.Graph({robot_body: robot_fire.body});

var graph_w = new RUR.Graph({robot_body: robot_water.body});

var graph_new = new RUR.Graph()

writeln(graph_f.neighbours( [4, 4]));

// some permutation of [[3, 4], [4, 3]]

writeln(graph_w.neighbours( [4, 4]));

// some permutation of [[4, 5], [4, 3]]

writeln(graph_new.neighbours( [4, 4]));

// some permutation of [[3, 4], [4, 3]]

// default robot is robot_fire,

// which was the first robot added

robot_fire.put();

writeln(graph_f.neighbours( [4, 4] ));

// -> [[4, 3]]

1. When we mention that move() could be used for Reeborg to go from one node to another, we assume that Reeborg faces the required direction. Later, we will introduce a different definition of a graph for Reeborg's World. ↩